Harvard Law School Students Speak Out Against ‘Coercive’ Employment Contracts

NOV 20, 2018 | COWORKER.ORG

A group of students, faculty, and alumni are working to make the law profession more equitable — one contract at a time.

Earlier this year, Harvard Law students started a petition on Coworker.org calling for an end to the “secrecy on harassment and discrimination” among law firms. They wanted the university to “require organizations recruiting on campus to allow victims of harassment and discrimination to bring their claims in a court of law.” As hundreds of individuals from the law community joined their efforts, they formed the Pipeline Parity Project — a coalition of Harvard students, faculty, and alumni working to “end harassment and discrimination in the legal profession”. In this interview, Harvard Law School students involved in the project open up about how they are using online campaign tools and data to keep law firms accountable to their employees and how students can improve the legal industry.

What inspired you to start the Pipeline Parity Project?

During our first year of law school, two big news stories broke. One exposed a years-long pattern of sexual harassment by prominent 9th Circuit judge Alex Kozinski. Another revealed that major law firms were forcing their employees — including summer interns and support staff — to sign away their civil rights as a condition of employment.

As students who came to law school to fight for justice, we were alarmed, although unfortunately not surprised, to see how women, people of color, LGBTQ people, and other marginalized groups are harassed, discriminated against, and generally disadvantaged within the legal profession. For those of us just beginning our careers in the law, it was disheartening — but it also served as a call to action.

A few dozen of us came together in the spring, committed to working to remedy these injustices, so that we might build a legal profession that is more inclusive and better equipped to ensure that our legal system truly promotes justice and equity for all. And then Brett Kavanaugh was nominated to the Supreme Court, which threw into relief the vital importance of what we are fighting for.

Now-Justice Kavanaugh began his career as a clerk for then-Judge Kozinski, although he (dubiously) claimed to know nothing of Kozinski’s pervasive and often public sexual harassment. Both were known to be feeder judges for recommending clerks to Kavanaugh’s former boss Justice Anthony Kennedy, who perhaps not coincidentally hired six times as many male clerks as female clerks during his time on the bench.

And of course, the multiple reports of sexual violence against Kavanaugh, as well as the allegations that he selected female clerks based in no small part on their looks, made it all the more important that we develop accountability mechanisms for misconduct in the judiciary. Brett Kavanaugh also began his career at Kirkland & Ellis, which for the past decade has used coercive contracts to keep its employees silent about potential claims of sexual harassment and discrimination.

It’s clear to us that these issues are deeply interrelated. Harassment and discrimination are narrowing professional pipelines for women, people of color, LGBTQ people, and many more. Not only does this affect those in the legal profession — it affects the law itself.

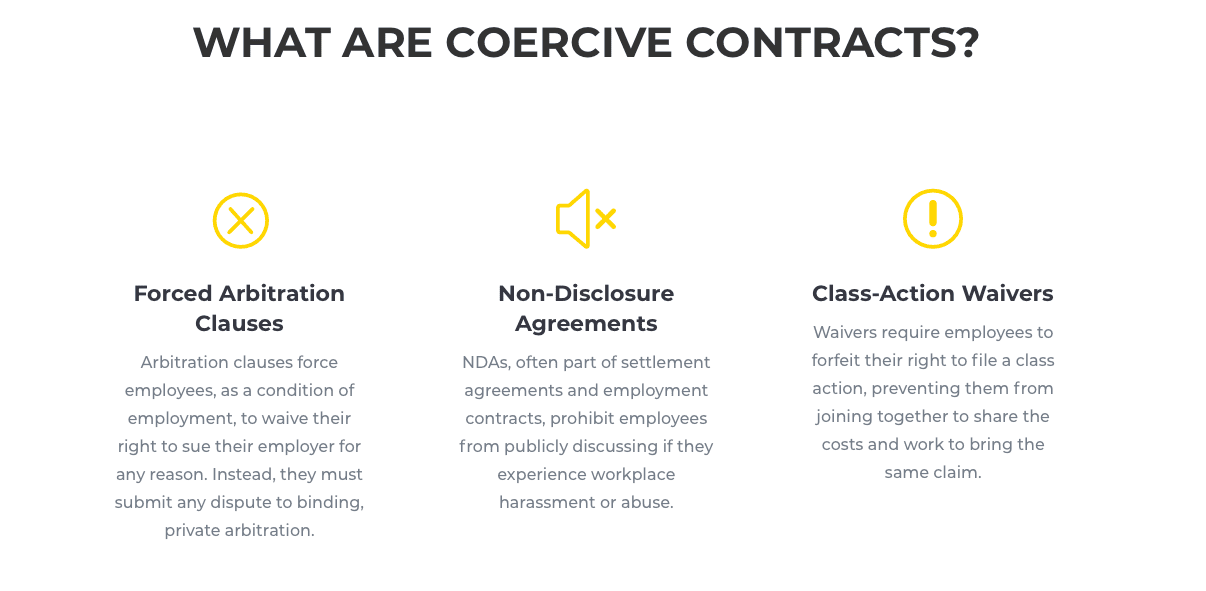

One of the main facets of the project is ending what you call “coercive contracts”. Could you tell me a little more about what you mean by “coercive contracts”?

Coercive contracts are employment contracts that require individuals to sign away their civil rights as a condition of employment. We see three major components to coercive contracts.

First, forced arbitration clauses prevent employees from taking their case to a court of law if they experience harassment or discrimination at work. Second, non-disclosure agreements mean that employees are never allowed to publicly discuss the harassment or discrimination that they experience, directly creating a culture of silence. Third, class action waivers prevent employees who have experienced the same or similar treatment from banding together to access justice.

Taken together, these provisions create environments in which the employer constantly has the upper hand, even if they engage in pervasive illegal behavior. We’ve seen throughout the #MeToo movement the ways in which these contracts prevent survivors of sexual harassment and discrimination from coming forward, and the same is true for victims of race-based discrimination and harassment, victims of harassment or discrimination based on sexual orientation, and others.

These contracts force people to choose between their job and their civil rights — and that’s not a choice that anyone should ever have to make.

One of the tactics that you used in your campaign is that you surveyed different law firms to see whether they had arbitration clauses, non-disclosure agreements, or class-action waivers in their employment contracts. What have you learned from collecting this data? How has it helped advance your cause?

Knowledge is power, and we learned a great deal from the initial survey results.While most major employers responded, a number of law firms refused to be honest with students about their employment practices and the nature of the contracts that they would be forced to sign. This was true even of firms such as Kirkland & Ellis and DLA Piper that we know with certainty are forcing employees to sign coercive contracts. We quickly saw the lengths to which firms were willing to go to hide their problematic practices.

With this information, students were able to make more informed decisions as they participated in the firm recruiting process this summer, and we know a number of people chose not to interview with firms that refused to answer the survey. Additionally, we’ve been able to center our organizing and education efforts on the employers that are the worst offenders. Finally, it’s helped us to explain the scope of the problem to students who might not already be aware.

How have law firms reacted to your survey questions? Were they receptive?

Most law firms had no objection to answering the survey — they don’t use coercive contracts, and were happy to let prospective employees know that. Unsurprisingly, the firms that have more to be ashamed of have been more reluctant to respond to the survey. In fact, a number of firms didn’t answer at all (or responded “Decline to State” for all questions), including firms like Kirkland & Ellis that we know with certainty utilize these provisions.

In some cases, like with Kirkland, we’ve had to disclose the information that we have ourselves, in order to provide students with the information that they need to make employment decisions that are in their best interest. In other cases, we’ve worked with the school’s administration, and they’ve followed up with firms to get the answers we need. While it’s disappointing to see major firms refuse to engage in even this most basic level of transparency, we’ve moved forward with the information that we have.

Prior to starting the Pipeline Parity Project, Harvard law students started a petition on Coworker.org. How did that petition evolve into the larger project?

In the spring, students from numerous law schools, including Harvard and Georgetown, started petitions on Coworker.org asking that our schools ban all employers who utilize coercive contracts. This was a critical start to our organizing efforts. It allowed us to get the word out to students, alumni, professors, and staff about these important issues, and showed us that there was intense desire within the legal community to force law firms to drop these contract provisions.

It was thanks to these petitions that 50 of the nation’s top law schools committed to sending out the survey discussed above, asking employers to disclose whether or not they rely on forced arbitration and other coercive practices. If they hadn’t felt the pressure of having hundreds of signatures on our petition, it’s highly doubtful that they would have taken this first step.

The Pipeline Parity Project is student led and student driven. How do you think students can keep companies accountable to their employees? From your perspective, what are the main challenges that you have faced driving this initiative as students?

As students at Harvard Law School, we’re in a very fortunate position. Legal employers want to recruit here, which gives us a certain amount of influence. It’s for exactly that reason that we’re doing this — we know that right now, we have a platform from which we might make the legal profession a bit more equitable, and we therefore have the responsibility to do what we can while we’re here. Once our classmates have gone to work for firms, they’ll actually have less influence as junior associates than they do now, as prospective employees. It’s a weird system, but one that allows us to do at least a bit to hold companies accountable to their current and future employees.

The biggest challenge that we face doing this as law students is the lack of time. We’re all taking full course loads and involved in other student organizations, journals, internships, etc. It can be a lot to handle in addition to our work with Pipeline. That’s part of why we’ve prioritized building such a strong team: it takes the burden off of any one individual, and makes sure that we’re all able to take care of our other work and ourselves while also prioritizing our organizing efforts.

What advice would you give to students who are looking to improve workplace conditions in the industries that they are hoping to pursue after graduation?

All of us have different career goals: some of us want to clerk, others want to work for law firms, and some of us aren’t interested in either but still care about workplace conditions. Our experiences show that the organizations we want to work for are not at all deterred from hiring us because we’re organizing around this. In fact, this work is the very reason why so many of us came to law school — to expand access to justice wherever we can.

Coworker.org is a global platform to advance change in the workplace. Our technology makes it easy for individuals or groups of employees to launch, join and win campaigns to improve their jobs and workplaces. You can start your own campaign about changes you want to see in your workplace on Coworker.org here — or contact us at [email protected] if you would like to discuss a workplace issue with our team.

CAMPAIGN STORIES