The Beginning of a 21st Century Labor Movement

AUG 30, 2018 | COWORKER.ORG

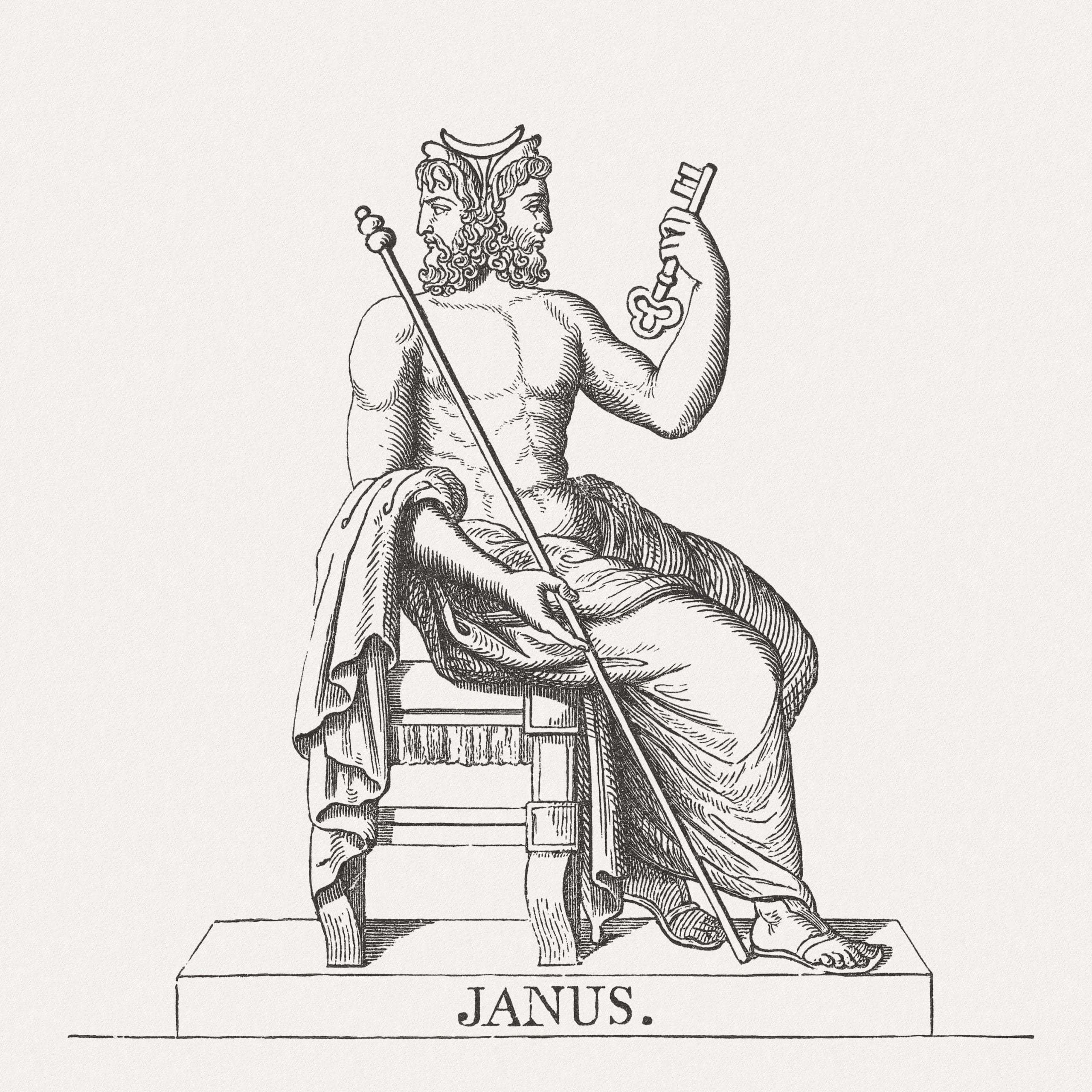

In ancient Roman mythology, Janus is the god of transitions, of beginnings and endings. With the Supreme Court decision on Janus v. AFSCME this past year, the U.S. labor movement as it has existed for a century will never be the same. But is it an ending? Or a beginning?

by Jess Kutch, Co-founder of Coworker.org

Too many workers in America know all too well how it feels to work jobs where you have no power over your schedule, your working conditions, or even your own body — whether it’s an experienced server in New York City’s posh Spotted Pig restaurant who silently endures routine groping and sexual harassment from her boss because, as she puts it, “The restaurant industry is lawless,” or a worker in a North Carolina foam seat manufacturing plant, who sustained neurological damage caused by the glue she used to seal foam seats together for brands like Broyhill and Ralph Lauren.

For the past 80 years, the path to workplace empowerment in America has been membership in a union. Union members earn higher wages — nearly 20 percent more per week on average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — and have stronger benefits, like family health care coverage and a pension. But the industry lobby groups executed a multi-decade strategy to undermine union membership, including deceptively named “Right to Work” legislation and a series of savage judicial attacks in courts across the nation, most notably this year’s Janus decision. Public sector unions are some of the largest and most powerful labor organizations left in America, and some experts estimate that this ruling could slash their membership rolls by more than 30 percent.

Many affected unions are implementing aggressive strategies to preserve their membership in the wake of Janus — that’s great. It’s also good news that some leaders are considering bold, long-term ideas like providing workers with portable benefits, union-administered unemployment insurance, sectoral bargaining, and even a federal jobs guarantee. But these solutions neglect the crisis at hand for today’s workforce, where the ability to push for higher wages and better working conditions is greatly diminished by employers, representatives in government, and, now, by the Supreme Court.

The beating heart of the American labor movement is not membership rolls or dues collection. It’s working people supporting one another. Acting together to experience their power and transform their working conditions, their lives, and their children’s futures. The labor movement and its allies can and should make good on that promise — right now — for non-union and union workers alike.

Many unions have spent much of the past few decades in a defensive crouch, clinging desperately to what remains. But think of the change we could effect if we explode our thinking on what a union is and whom it protects. We can help all workers organize in their workplaces, with or without the benefit of a formal union.

A handful of ideas to get us started:

Convert underused union halls into community spaces — Non-union workers and union workers alike could reserve and use these spaces for meetups with co-workers, community activism, and social gatherings. Workers should be able to search online for the nearest union hall and instantly book space to use.

Set up a CrisisTextLine-like service to assist workers — Make it easy for workers to receive free legal guidance on workplace problems and get access to information and support. And since many lawyers won’t even pursue workplace claims because they aren’t lucrative enough, we can route workers through to alternatives like counseling, regulatory agencies, or advocacy groups.

Independent strike funds — A way for non-union workers to go on strike for better wages or working conditions. The particulars of such a fund would require time and attention to sort out, but the result could be dramatic. A Red Cross-like relief fund could mobilize when workers are on strike, helping connect people to community resources, financial assistance, and legal guidance, while rallying public support for their efforts.

An institute for the future of labor — Our workplaces are being transformed by technology, but little is understood about its impact on working people. We should invest in research, analysis, and ideas that position the well-being of workers and our communities at the center of this discussion. How is algorithmic management preventing workers from advocating for themselves? Could emotional AI software be used to surveil workers engaging in protected concerted activity? Should rideshare drivers own and profit from their driving data? And finally, what policy proposals might respond to these changes wrought by technology?

A ‘Princeton Review’ for Employers — When people consider new job opportunities, they often lack verified, independently sourced information about an employer. Crowdsourced information on sites like Glassdoor can be of value, but there’s also a need for expert-vetted information on an employers’ wage scale, working conditions, diversity metrics, safety violations, benefits, and more. It’s strange that in 2018, when data is an increasingly sought after commodity, employers do not publicly disclose basic data on what kinds of standard benefits they offer employees.

We created Coworker.org as a space to wrestle with these questions and support workers who are experimenting with power-building strategies for today’s economy. And we’ve found that workers are hungry for this opportunity. On our platform alone, hundreds of thousands of people have engaged in workplace activism, resulting in changes that have impacted millions. Employees at a major retailer won nationwide wage increases. Baristas and fast food workers won updates to their company’s dress codes. Tech workers at a major internet company won changes to how their company addresses harassment and abuse of employees. And new people are stepping forward each week.

What can we do to support people as agents of change at work? What interventions can be staged so that a small group of workers can improve their jobs and workplaces today, not in 10 or 20 years? We can begin by building and connecting workers to 21st century organizing platforms, and urging institutions and individuals passionate about addressing income inequality to funnel capital to these new worker voice models.

The Wagner Act of 1935 required the formal support of a majority of employees in order to form a union. But prior to the passage of Wagner, workers had never relied on the “counting of noses,” as then-Labor Secretary Francis Perkins termed it. Those workers simply joined together, marched into the boss’s office and started negotiating for higher wages and better working conditions. But labor leaders agreed to this strict counting in exchange for more security and enforcement, for a seat at the table in policymaking. That deal is now dead. But Janus offers an opportunity to imagine a new labor movement — one that no is longer confined by its 20th-century union past, but absorbs its new role as a facilitator, a catalyst, and platform for workers to affect change. And that’s why this isn’t just an ending — it’s a promising new beginning.

Coworker.org is a global platform to advance change in the workplace. Our technology makes it easy for individuals or groups of employees to launch, join and win campaigns to improve their jobs and workplaces. You can start your own campaign about changes you want to see in your workplace on Coworker.org here — or contact us at [email protected] if you would like to discuss a workplace issue with our team.

WORKPLACE POLICY RESEARCH