How to crowdsource employee data to promote salary transparency

Lessons from Art + Museum Transparency

SEPTEMBER 6, 2019 | COWORKER.ORG

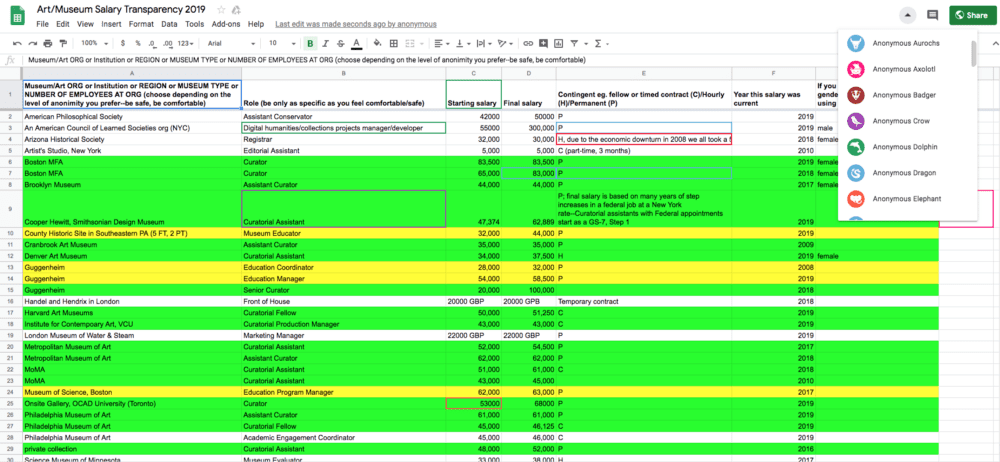

In May 2019, a group of art workers and museum workers initiated a crowd-sourced Google spreadsheet where thousands of industry professionals self-reported information about their salaries. Calling their group Art + Museum Transparency, they didn’t stop there.

Later in the summer, they created a separate crowd-sourced spreadsheet to surface data about internships at art institutions and museums. The data revealed a number of institutions that rely on unpaid and underpaid interns — a practice that Art + Museum Transparency says limits “the pool of emerging professionals to a privileged few and inhibit[s] inclusivity and diversity in arts and museum spaces.”

In a post from July, the group wrote:

“We, and our colleagues across museums and arts organizations of all types, want more than anything to see our institutions’ professed values become realities… In a moment when leadership usually favors new building projects, we are agitating for a seat at the table and fighting for sharply divergent visions for the future of our organizations.”

The spreadsheet took off during a wave of unionization of staff at a number of prominent museums throughout 2019 including the Guggenheim, the Tenement Museum, New Museum, the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York and the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, Washington.

In addition to inspiring discussions at institutions across the country and gathering lots of media coverage, the effort has also already inspired employees in other industries who have undertaken similar salary transparency initiatives. For example, there’s a current effort titled “What do the people who teach college get paid?” to compile data about salaries for adjunct professors in colleges and universities. (As you’ll see below, this effort brings the tactic of data-gathering salaries full-circle for art and museum workers who were initially inspired by a previous initiative from adjuncts.)

We asked organizers of Art + Museum Transparency to share some thoughts about their efforts and what they’ve learned.

What inspired you to create the initial spreadsheet of salaries in the art and museum sector?

We are a group of friends and colleagues in the arts and museum sectors and like everyone in our workplaces, we talk constantly about frustrations big and small. Without going into too much detail, things in some of our workplaces had gotten really bad and we decided we had to do something more than just talk about it. The idea for a crowdsourced salary spreadsheet came, most directly, from the Adjunct Project, a crowdsourced salary spreadsheet for adjuncts in higher-education, started by Joshua Boldt in 2012. With all of the issues in our workplaces, we became convinced that salaries, and salary transparency, was a nexus where many issues of equity came together. In that we’ve been inspired by those foregrounding pay inequities in the sector — Kimberly Drew and PoWArts, among others too.

How did you settle on using a Google spreadsheet and what were some of the tools and strategies you used for distributing the spreadsheets?

The initial salary spreadsheet was directly inspired by the Adjunct Project, which also used Google. We liked that the Google spreadsheet was editable in real-time and shareable. At first, the idea was to share a completely editable spreadsheet, and in the first weekend, hundreds of contributors built out the data structure, adding columns for different kinds of information that we had never considered. After a few days there was so much activity, and data was repeatedly deleted or disorganized by accident, that we decided to close direct editing. From then on, contributors have added content through a google form. The spreadsheet itself is locked. We distributed it through our own immediate social circles, through email and texts, and then it quickly took on a life of its own.

As interest grew, we received interview requests and the resulting press coverage brought more folks to the spreadsheet. Within the first week, we also set up a Twitter account (@AMTransparency) and a gmail account ([email protected]). We created the Twitter account because we realized that we needed to have some permanent presence online where people could find the links to the spreadsheets — we were constantly getting that question. So a Twitter bio seemed like a good place for that. We have also used Twitter to periodically address issues folks have raised in their submissions and to solicit continued submissions.

The internship spreadsheet was slightly different. We had been working on the idea and pitched an op-ed to ArtNews, where we announced its launching.

Were there particular considerations you undertook to ensure a diversity of responses and data in your spreadsheets?

From the beginning, we felt strongly that submitters would be more honest and forthcoming if they could submit anonymously. As folks working in the field, we knew the workplace cultures of fear and precarity facing many of us so we knew that letting folks decide on the level of anonymity they were most comfortable with was essential. We have stated on both spreadsheet forms: “Be Safe, Be Comfortable” and that is really important to us. Even when disclosing one’s own salary information is a legally-protected right, we know that there are both real and perceived risks and we wanted everyone to feel that they could be as honest as possible.

We also take note when certain types of jobs or certain geographic areas are underrepresented on the spreadsheets and seek to encourage submissions in those areas, via Twitter or our own networks. There are still many areas that need work, for example, HR professionals in museums and arts organizations. There are very few who submitted to the salary spreadsheet and we hope to see that change.

Have you heard any examples of retaliation faced by people who contributed to the spreadsheets?

We have, but only a few. We’ve received emails from people asking us to remove their data or to help them anonymize it further, after they’ve received negative feedback at work. We’ve wanted to respect the anonymity of these folks, so we haven’t asked for further details about where they work or the nature of this feedback. We believe strongly that everyone submitting should be safe, and are always happy to make the requested changes.

Was there information revealed in your work that surprised you and/or confirmed what you already suspected about your industry?

The mass of data collected has provided a bird’s eye view of the industry and it largely confirms our experiences in our own organizations and our impressions of the problems that are systemic and deeply entrenched. We were not prepared for the individual stories that we have heard from people who have reached out to us via email, Twitter DMs, or in person. Many of the stories we’ve heard are quite horrific, detailing situations of extreme exploitation and abuse, and they’ve convinced us of the need for dramatic changes across the industry.

Have you heard of ways that individuals or groups of employees have used the salary transparency to negotiate for changes within their institutions?

We’ve heard from a few folks that received unexpected raises this summer and attributed it to the spreadsheet. Who knows how direct the relationship was, but it warmed our hearts to hear it. Personally, we know people who have used the salary data on the job market, either to inform their salary negotiations or to preclude applying for underpaying jobs. And we know many, many people who have used the spreadsheet and its prompt to submit their information to start conversations in their workplaces with colleagues or managers around necessary change.

What advice would you give to people in other industries who might be interested in taking on salary transparency efforts?

We’d heartily encourage it and advise them to plunge in. Crowdsourcing the information is extremely effective, as long as folks can feel safe and comfortable in submitting their info. If people have any questions about what worked and what didn’t work for us, we welcome them to reach out to us via email or Twitter.

Anything else you would like to share?

Just that it’s been extremely exciting to see all the energy and solidarity building in real-time around the spreadsheet and issues of wage equity in our arts organizations and museums. This is an issue that many have been working to address for a long time, and there’s still a long way to go, but we love the momentum and conversations we see happening right now and want to support and encourage them any way we can. We are here for exactly that.

Coworker.org is a global platform to advance change in the workplace. Our platform makes it easy for individuals or groups of employees to launch, join, and win campaigns to improve their jobs and workplaces. You can start your own campaign for changes you want to see in your workplace here at Coworker.org, or contact us at [email protected] if you would like to discuss a workplace issue with our team.

LABOR WORKERS RIGHTS STRIKE